Life magazine has posted a trove of photographs of Vladimir Nabokov in 1959, a year after the first U.S. publication of Lolita. From the photo captions:

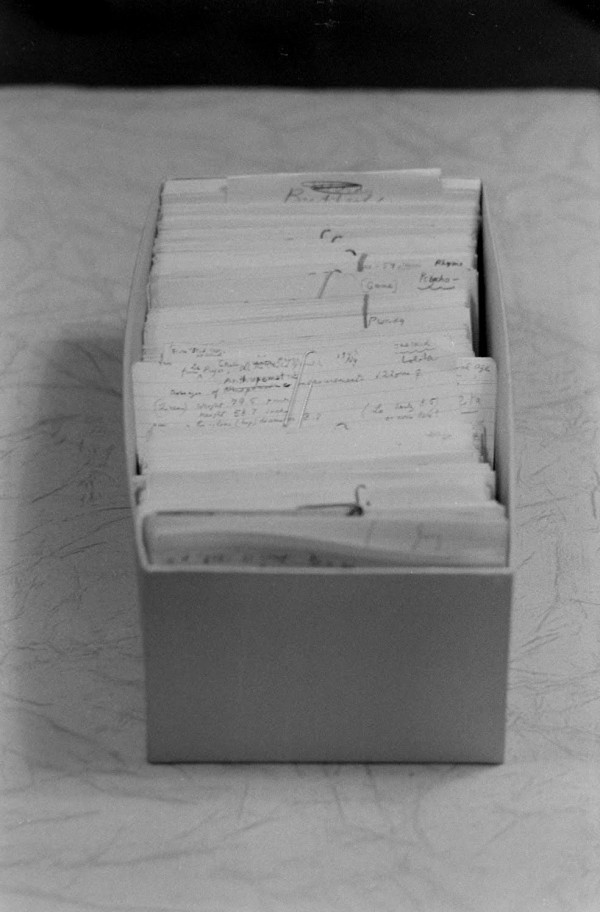

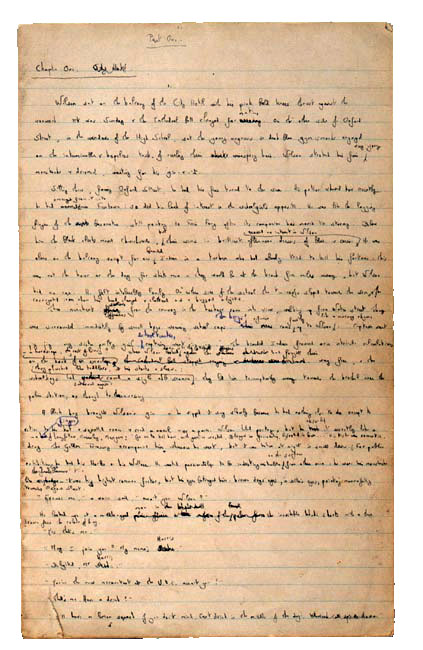

Nabokov wrote most of his novels on 3″ x 5″ notecards, keeping blank cards under his pillow for whenever inspiration struck. Seen here: a draft of Lolita.… Near the end of writing Lolita, Nabokov became dissatisfied with the work and tried to burn his notecards. Vera [his wife] stopped him.