Robert Olen Butler has said,

The one thing that other aspiring artists have over writers is that many of them can view their mentors at work. A painter can sit at the back of a studio and watch her mentor paint, a ballet dancer can watch his mentor rehearse and perform. But you can’t really observe the creative process of a fiction writer. It’s never been seen.

It is a cherished fantasy of writers: if only a wise mentor could be with me at the moment of creation, looking over my shoulder, teaching me how to apply the chisel to the stone. The essence of a writer’s work is mysterious even to himself. Ask any writer how he creates his stories, what is happening inside his head as he types away madly, and watch him stammer. The only honest answer is “I have no idea.”

Olen Butler tried to capture the process on tape once. He recorded a series of videos for creative-writing students in which he sat at his computer and composed a short story. He would stop every sentence or so, describing the word choice or plot decision he was mulling, the options available, the reasons he might go one way or the other. The experiment did not really work. The videos are fine as a pedagogical tool and I admire Olen Butler for trying to capture the ineffable, but the constant interruptions seemed to short-circuit the creative process, and the story he wrote frankly was not very good.

If anything, Olen Butler’s experiment demonstrated that writing is intractably internal. It can only happen invisibly in the writer’s unconscious mind. The moment you look at it, it disappears. The moment you say to yourself, “I am writing,” you stop.

That is one reason why creative writing is so hard to teach. A writer can only show the product of his work for an after-the-fact review. He submits his pages to be judged, thumbs up or down, often in a “workshop” (the very name bespeaks writers’ desperation to recreate the studio experience available to other artists). His inadequacies cannot be corrected, only pointed out, because there is no “correct” way to achieve a given literary effect. Technique must be learned by trial and error. No one knows how it is done, even fellow writers; they only know it when they see it. It is as if a tennis coach could only tell a talented young player “you won” or “you lost.”

Still, we try. I have a voyeuristic interest in how other writers work. So when I run across a passage like the one below, from Michael Salter’s Charles Dickens, I stop to study it. This is the closest we can get to Olen Butler’s fantasy for young writers: a chance to look over the great man’s shoulder as he works. If you are not a writer, you may as well stop reading. The subject of how Dickens outlined his novels will not interest you. But if you are a writer, this sort of detail is gold.

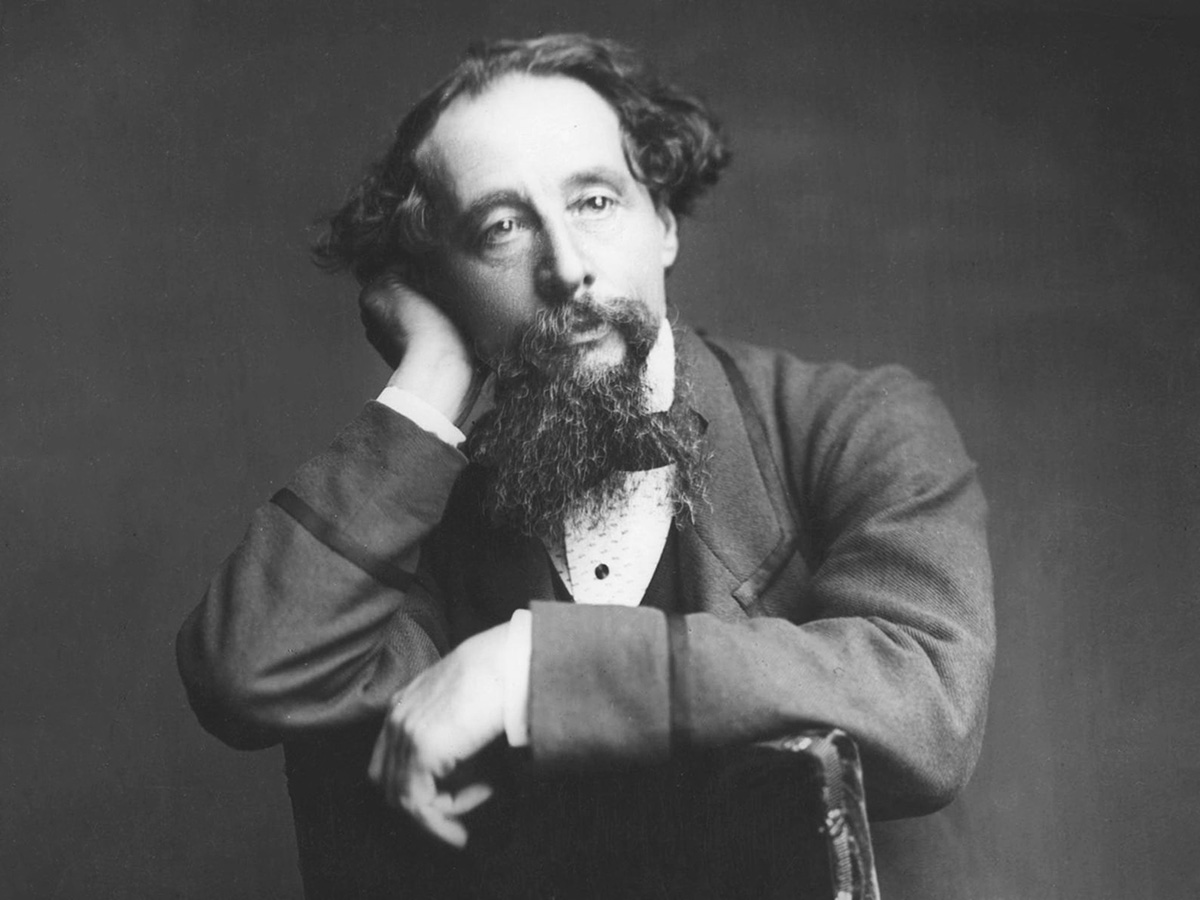

The year is 1846. Dickens is 34 and already firmly established as England’s best and most celebrated writer. He has left London for the peace and quiet of Lausanne, Switzerland, to begin his novel Dombey and Son.

Dombey is the first Dickens novel for which there exists a complete set of preparatory notes for each monthly number (an isolated set, quoted above, exists for Chuzzlewit IV), a working practice Dickens followed for all his subsequent novels in this format, as well as for Hard Times which was published as a weekly serial but planned in five monthly numbers.

For each number he prepared a sheet of paper approximately 7×9 inches by turning it sideways, with the long side horizontal, dividing it in two, and then using the left-hand side for what he called “Mems.” These were memoranda to himself about events and scenes that might feature in the number, directions as to the pace of the narrative, particular phrases he wanted to work in, questions to himself about whether such-and-such a character should appear in this number or be kept waiting in the wings (usually with some such answer as “Yes,” “No,” or “Not yet” added later) — in short, what has been succinctly described as “brief aids in decision making, planning and remembering.” Among the “General mems for No 3,” for example, we find that wonderful image for little Paul’s desolation at Mrs. Pipchin’s, “— as if he had taken life: [sic] unfurnished, and the upholster were never coming” … and “Be patient with Carker — Get him on very slowly, without incident” (DS XII).

…

On the right hand side of the sheet Dickens would generally write the numbers and titles of the three chapters that make up each monthly part and jot down, either before or after writing them, the names of the main characters and events featuring in each chapter. with occasionally a crucial fragment of the dialogue like little Paul’s “Papa what’s money?” in chapter 8 [of Dombey and Son], or a note of significant events like “Death’s warning to Mrs Skewton” in chapter 36.

— Michael Slater, Charles Dickens, pp. 258-59

Here are Dickens’ “mems” for the first chapter of Little Dorrit, which opens with two men in a dank prison cell on a broiling summer day in Marseilles.

Waiting Room? No

Office? No

French Town? Yes

Man from China? Yes

Prison? Yes

Quarantine? Yes— Source: Modern Philology, August 1966 (oh, the wonders of the web!)

I look at these scant notes and I see a writer accustomed to improvising in the moment. Only the bare essentials are drawn in beforehand. He may simply have known where he was going well enough that he did not feel the need to create a detailed outline (as I do). But Dickens must have known, too, that no matter how much planning has been done, when you finally sit down to write, it is time to put away your outlines and research, and keep only a few simple notes on the desk before you. The real work of creating will only be distracted by all this external stuff.

Also, I look at that joyous little double-underline when he hit on the idea of setting the scene in a prison cell and I feel his happiness. How many hours went into that breakthrough? How much of the writer’s private triumph is expressed in that little emphasis? Go, Charles!

Image: Detail from Dickens’ portrait by photographer George Herbert Watkins, ca. 1861. (The original, full portrait is here. Look here for more information.)

“The essence of a writer’s work is mysterious even to himself”: I like that. This has a lot of truth in it.

Are you aware of Harry Stone’s “Dickens’ Working Notes for his Novels”? I believe it has got a painstaking analysis on the issue.

I have not seen Harry Stone’s book, but I will seek it out. Just skimming it on Google Books (those brazen defilers of copyright law), I was amazed to find this facsimile of the very “mem” I quoted! Amazing. Thank you.