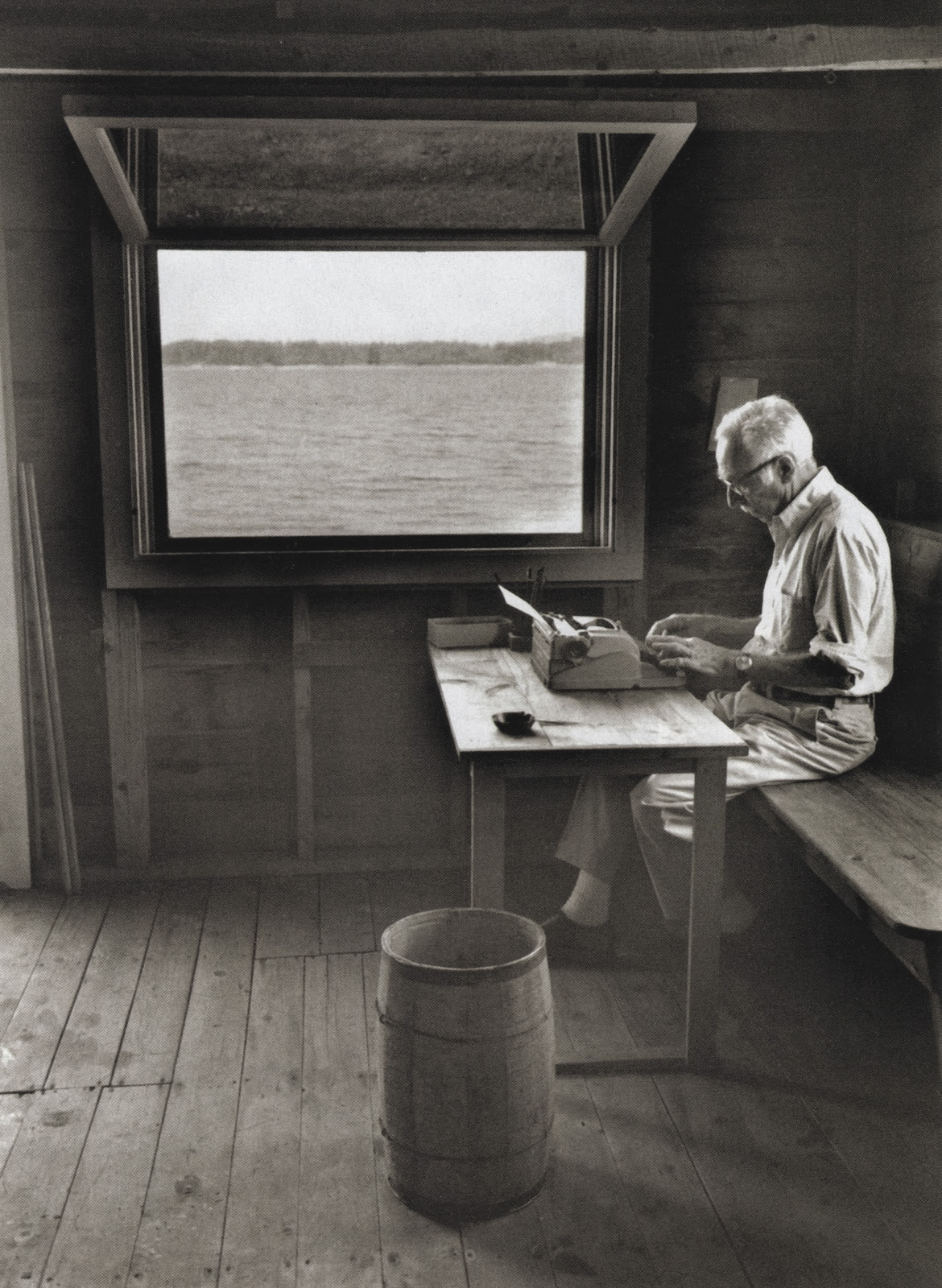

E.B. White worked in a 10- by 15-foot wooden shack, originally built as a boathouse, at his home in North Brooklin, Maine. Photo by Jill Krementz. A visitor in 2017 wrote,

The small boathouse was down a gentle slope, just a few paces from the water … It looked much like it did in the famous Jill Krementz photo of White working in it: the bench; the writing table; the blue metal ashtray; a croquet-case-turned-cupboard; a list of New Yorker “newsbreak” headlines pinned to the wall. … [The] Whites’ caretaker would transport the typewriter down to the boathouse in a truck, while Andy walked, and pick it up at the end of the day.

In 1949, reviewing a book on writing by an author who “gets a great deal done,” White wrote (in the New Yorker’s distinctive we/our style):

Now turn for a moment to your correspondent. The thought of writing hangs over our mind like an ugly cloud, making us apprehensive and depressed, as before a summer storm, so that we begin the day by subsiding after breakfast, or by going away, often to seedy and inconclusive destinations: the nearest zoo, or a branch post office to buy a few stamped envelopes. Our professional life has been a long, shameless exercise in avoidance. Our home is designed for the maximum of interruption, our office is the place where we never are. From his remarks, we gather that Roberts is contemptuous of this temperament and setup, regards it as largely a pose and certainly a deficiency in blood. It has occurred to us that perhaps we are not a writer at all but merely a bright clerk who persists in crowding his destiny. Yet the record is there. Not even lying down and closing the blinds stops us from writing; not even our family, and our preoccupation with same, stops us.