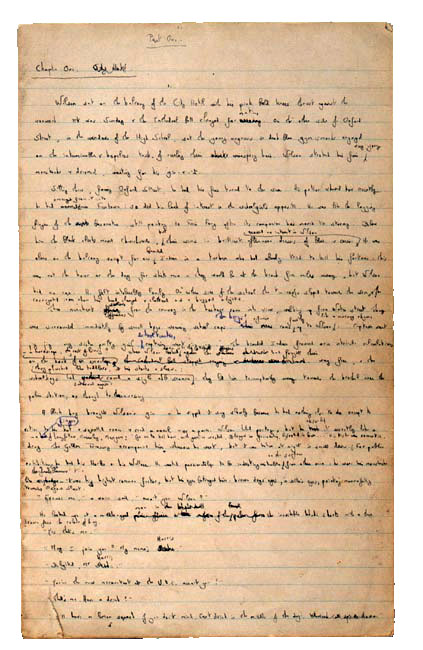

Recently I wrote a short appreciation for the Rap Sheet of George V. Higgins’s definitive Boston crime novel, The Friends of Eddie Coyle. The piece will run soon as part of the Rap Sheet’s terrific Friday series, Books You Have to Read, which celebrates forgotten (or never properly appreciated) crime novels. [Update: My article on the novel is now up. You can find it here.]

Fortuitously, Criterion just released a pristine new restoration of the 1973 film version of The Friends of Eddie Coyle, and it is not to be missed. The Criterion DVD brings back a forgotten classic and the best movie about Boston ever.

Let’s be honest: there aren’t that many great movies about Boston, particularly crime stories, though the city has bred more than its share of crime novelists. There are some good movies set in Boston that could as easily take place elsewhere without losing much; The Verdict comes to mind. But movies that aim to capture this city’s unique personality — as, say, L.A. Confidential and Chinatown do for Los Angeles? Or Goodfellas and Once Upon a Time in America are unmistakably New York stories? Those are rare.

The serious competition is all recent. Good Will Hunting is fun but overrated. (Watch it again.) The Departed is just not a serious movie, and anyone who believes Jack Nicholson or Leonardo DiCaprio would last five minutes in Whitey Bulger’s world really ought to turn off the DVD player and come out into the world for a while.

The only real challenger for the title of best Boston movie is Mystic River. But put the two films side by side and Mystic River looks like Eddie Coyle lite — Boston as Californians might imagine it. Mystic River is just too much of everything: a melodrama, pretty to look at, with gorgeous swooping helicopter-cam shots of the city skyline and a platoon of glamorous stars, all of them strenuously, visibly acting. These are the sort of big, emotive performances we now recognize as Oscar bait, Sean Penn’s in particular.

The Friends of Eddie Coyle is the real thing. Quiet and dingy, a series of terse conversations in dim bars and gray, leafless parks. It is an ensemble piece, despite having a big-ticket star in Robert Mitchum. Voices are rarely raised. Only two fatal shots are fired. This is the reality of small-time crime life: not high drama, but a wary, exhausting series of risky transactions dimly understood even by the thick-headed hoods on the inside.

With any Boston movie, we have to consider how the difficult Boston accent is handled, too, and here Mystic River flops badly. I saw it in Boston in a theater full of Bostonians, and the audience seemed to require subtitles to understand what the hell these people were saying. Eddie Coyle has a few wobbly moments but mostly gets it right. Alex Rocco, now remembered mostly as Moe Greene in The Godfather, plays a convincing Boston hoodlum. He should: as a pudgy kid named Bobo Petricone he hung around on the periphery of the fearsome Winter Hill Gang.

Eddie Coyle is not perfect by any means. A lot of the dialogue is lifted straight from the novel (that Higgins did not get a screenwriter credit is a travesty), and some of those lines don’t work as well in the actors’ mouths as they do on the page. And the seventies tics — the wah-wah soundtrack, the groovy idioms, “man” and “lover” and so on — can be a bit much, though you might go in for that sort of thing.

It may be, too, that the film appeals to me as a time capsule of a city I remember. To a kid who grew up in Boston, it is a kick to see Barbo’s furniture store. (Any New Englander of a certain age can sing the Barbo’s jingle, which played on car radios incessantly.) And to revisit the old Boston Garden, where Eddie watches the sports god of my childhood, “number four, Bobby Orr — what a future he has.” Just seeing Boston in late fall — completely drained of color, the trees all bare, the grayed-out sunless sky, the people dressed in drab — is enough to make me feel poignant and murderous.

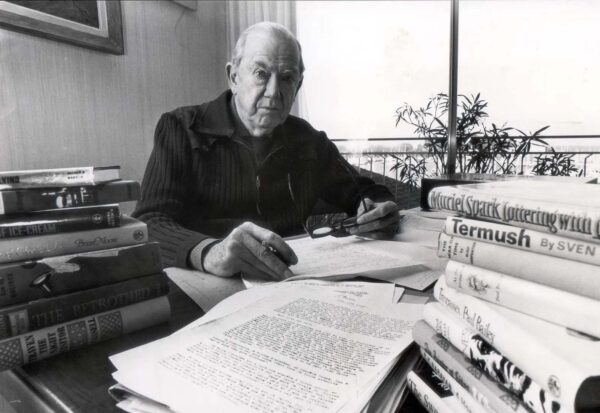

But the main thing The Friends of Eddie Coyle has going for it is Mitchum, speaking the incomparable lines of George Higgins. Mitchum is not the Eddie Coyle of the book. Even in his brokedown fifties, Mitchum is too big and handsome for that. He can’t smother his leading-man charisma enough to quite become a small-time loser like Eddie. So this Eddie Coyle is Mitchum’s own creation. The booklet that accompanies the new Criterion DVD — which alone is worth the price of the disk — says that Mitchum was first offered the part of Dillon, the two-faced bartender. That part instead went to a then-unknown Peter Boyle. Good thing. Mitchum gives the the best performance of his life. He is as quiet and understated as Sean Penn is actorly. There is not a hint of the preening movie star anywhere in his performance. Watch this clip and notice how little Mitchum moves his body or alters his expression, how he communicates a lot while “signaling” very little. The effect is completely convincing. That voice, that smirking wised-up manner — true Boston.