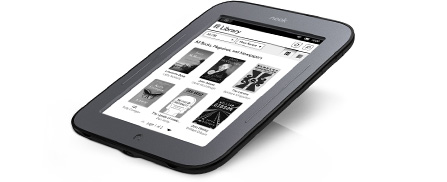

A couple of days ago, my wife gave me a Nook for my birthday. It is the first e-reader I have owned, and so far I have been very impressed.

A couple of days ago, my wife gave me a Nook for my birthday. It is the first e-reader I have owned, and so far I have been very impressed.

Until now, I have not been willing to make the switch to ebooks. The first-generation e-ink screens always looked murky, and the machines themselves — the early Kindles especially — were just plain ugly.

But the new Nook, which B&N has saddled with the dreary name Nook Simple Touch Reader, has been a revelation. The 6-inch e-ink screen is very clear and bright. The case has an elegant, simple design. Clearly B&N has studied the uncluttered look of touch-screen iPods. They’ve stripped away virtually everything but the screen itself and a comfortable, thick, grippy, rubbery bezel to hold it by. No more dual screens or physical keypads. There are still a few well-disguised buttons on the case (on the front, a home key and page-forward and page-back buttons, plus a power button on the back), but the Nook is primarily controlled by its touch screen.

About that touch screen: All e-ink displays rely on some secondary technology to make them touch-sensitive. Early e-readers used a physical layer overlaid on the e-ink display, but the result was to make the screen hazy and dull. The new Nook’s touch screen uses infrared sensors rather than physical pressure to determine where your finger is. The sensors are arrayed unobtrusively around the edge of the screen. So it is not a true touch screen. In fact, I have found you can turn the page without quite making contact with the surface of the screen, so long as your finger comes close enough to trip the sensors. The end result is not as good as back-lit displays like the iPad. The Nook’s touch screen is less responsive, less precise. But you get used to it quickly. I have found typing and swiping on the Nook very comfortable. And the tradeoff is well worth it for the benefits of e-ink: a very sharp display without the eye fatigue caused by back-lighting, plus very, very long battery life (two months for the Nook, according to B&N). The only concern with the Nook’s touch-screen system is that over time the screen is likely to get dirty and smudged from my oily fingertips, and of course an e-ink screen can’t be cleaned with Windex.

Enough about the hardware. What about the experience?

I have found reading on the Nook absolutely exhilarating. Halfway through my first ebook, Colm Toibin’s wonderful The Master, I actually prefer it to physical books. Until now I have sympathized with the traditionalists who cherish the tactile experience of a “real” book. But the Nook has changed my mind. It is so much lighter and easier to hold than a 400-page book. To hold a big book effortlessly with one hand is a completely new experience. The ability to adjust the font, type size, and line spacing is also wonderful, since viewing conditions change throughout the day.

Yes, an ebook is less beautiful than a traditional book. Yes, something is lost when we stop thinking of “books” as physical objects. But I’d underestimated the benefits of going digital. So, to the traditionalists: It is not about which format is “better.” It is about adding a new format for books, not replacing the old format with a new one.

My sunny response to the Nook may be affected by the fact I am a writer. To me, my own novels have never been the paper-and-ink objects that readers buy; those are just the containers in which the novels are shipped. And for the most part the packaging is not my own work. What I create is just the string of words inside the covers, the text. All the rest — the cover art, the jacket copy, the typeface, the page layout — is all done by the publisher. To see all that stripped away, leaving just the text itself, returns the book to the essential thing that the writer himself made. Anyway, every writer is used to seeing books this way, as unadorned text on a screen — that is how they look as they are being written.

Reading on my Nook, I feel surprisingly encouraged about the future of publishing. The device itself generates excitement about books. Even now, I can’t wait to pick up the Nook and get back to The Master. I can’t wait to buy more ebooks, too. After so many years of reading, it is exciting to experience books in this new way. I suspect I will end up reading more than I have before. During those evening hours after the kids go to sleep, when I might have turned on the laptop and drifted off in a web trance, now I am likely to turn on the Nook instead for a quieter, more focused, less distracted reading experience. (Caveat: when I’m really writing well, I can’t read anything at all, so we’ll have to wait and see whether I actually wind up reading more books.) Surely I’m not alone in reacting this way. I can easily imagine the inexorable adoption of ebooks triggering more reading, not less, hardly the end-of-days scenario the doomsayers have been going on about.

Ebooks are a different way to experience a novel. In some ways better, purer. Just you and the text. There is complete privacy — no signaling to others about what you are reading, no book cover to invite them into the experience, to trigger a conversation. And no book designer to frame the experience for you, to color your perception of the book with an “important” cover or deckle-edged pages or heavy paper. Just the words, the happy dream of the story itself. I like it.

I’ll let you know whether I still like the ebook experiment after a while, when the novelty has worn off. But so far, so good.