The publisher has assembled a fun (and free) kit for book clubs that includes a note from me, discussion questions, even cocktail suggestions. You can download the PDF here. [Edit 2.6.24: An updated book club kit with the new paperback cover art is here.]

On sale now!

Today is publishing day — All That Is Mine I Carry With Me is officially on sale. We’ve been banging the drum for this book already. There are podcasts, essays, live appearances, and more on the way. And we’re doing as much social media as we can (including a peek at my office on Instagram). But there is no substitute for a book recommendation from a trusted friend. So if you’ve read the book and enjoyed it, please pass the word. Thank you to everyone who has helped in this effort, and I hope I’ll see you out on tour!

(Want to buy the book online? My publisher has gathered up links to all the most popular booksellers here.)

Ian McEwan interviewed

The Bic Pen

Today I learned … that the classic Bic pen (it is actually called the Bic Cristal) is in the Museum of Modern Art.

Familiars

Familiars is an extraordinary series of classic texts reinterpreted by modern artists, from English publisher Four Corners Books. “Each book is different in style and format, according to the needs of the artwork and the text.” Very cool.

New Novel Coming March 2023

Some exciting news: after a long silence, I have a new novel at last. All That Is Mine I Carry With Me will be published on March 7, 2023. I will have much more to say about the book as the pub date draws near, but for now I just wanted to share the news. Thank you all for sticking with me through this long process.

Update 8.18.22: If you just can’t wait, my publisher has some information and links to pre-order the book here.

The Myth of a Golden Age of Books

Amazing fact of the day: in 1931 there were just 500 or so real bookstores in America, and two-thirds of the country had no bookstores at all.

In the entire country [in 1931], there were only some four thousand places where a book could be purchased, and most of these were gift shops and stationary stores that carried only a few popular novels.… In reality, there were but five hundred or so legitimate bookstores that warranted regular visits from publishers’ salesmen (and in 1931 they were all men). Of these five hundred, most were refined, old-fashioned ‘carriage trade’ stores catering to an elite clientele in the nation’s twelve largest cities.

Furthermore, two-thirds of American counties — 66 percent! — had exactly zero bookstores. It was a relatively tiny business centered in the urban areas of the country. Did some great books come out back then? Of course! But they were aimed only at the tiny percentage of the country that was visible to publishers of the time: sophisticated urban elites. It wasn’t that people couldn’t read; by 1940, UNESCO estimated that 95 percent of adults in America were literate. No, it’s just that the vast majority of adults were not considered to be part of the cultural enterprise of book publishing. People read stuff (the paper, the Bible, comic books), just not what the publishers were putting out.

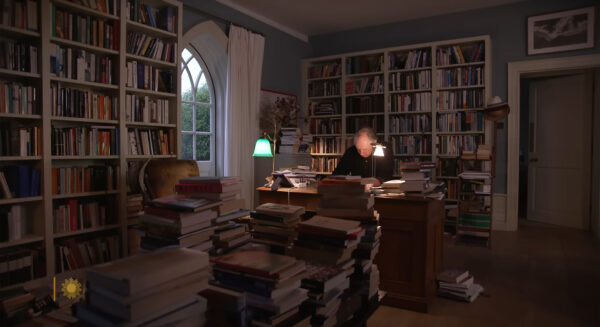

David Milch at work

By design, Milch wrote “Deadwood” under a gun-to-the-head deadline, regularly composing dialogue the day before a scene was to be shot. Milch is the only writer I have ever watched, at length, write. I sat in a dimly lit, air-conditioned trailer as Milch—surrounded by several silent acolytes, of varying degrees of experience and career accomplishment—sprawled on the floor in the middle of the room, staring at a large computer monitor a few feet away. An assistant at a keyboard took dictation as Milch, seemingly channeling voices from a remote dimension, put words into (and took words out of) the mouth of this or that character. The cursor on the screen advanced and retreated until the exchange sounded precisely right. The methodology evoked a séance, and it was necessary to remind oneself that the voices in fact issued from a certain precinct of the fellow on the floor’s brain.