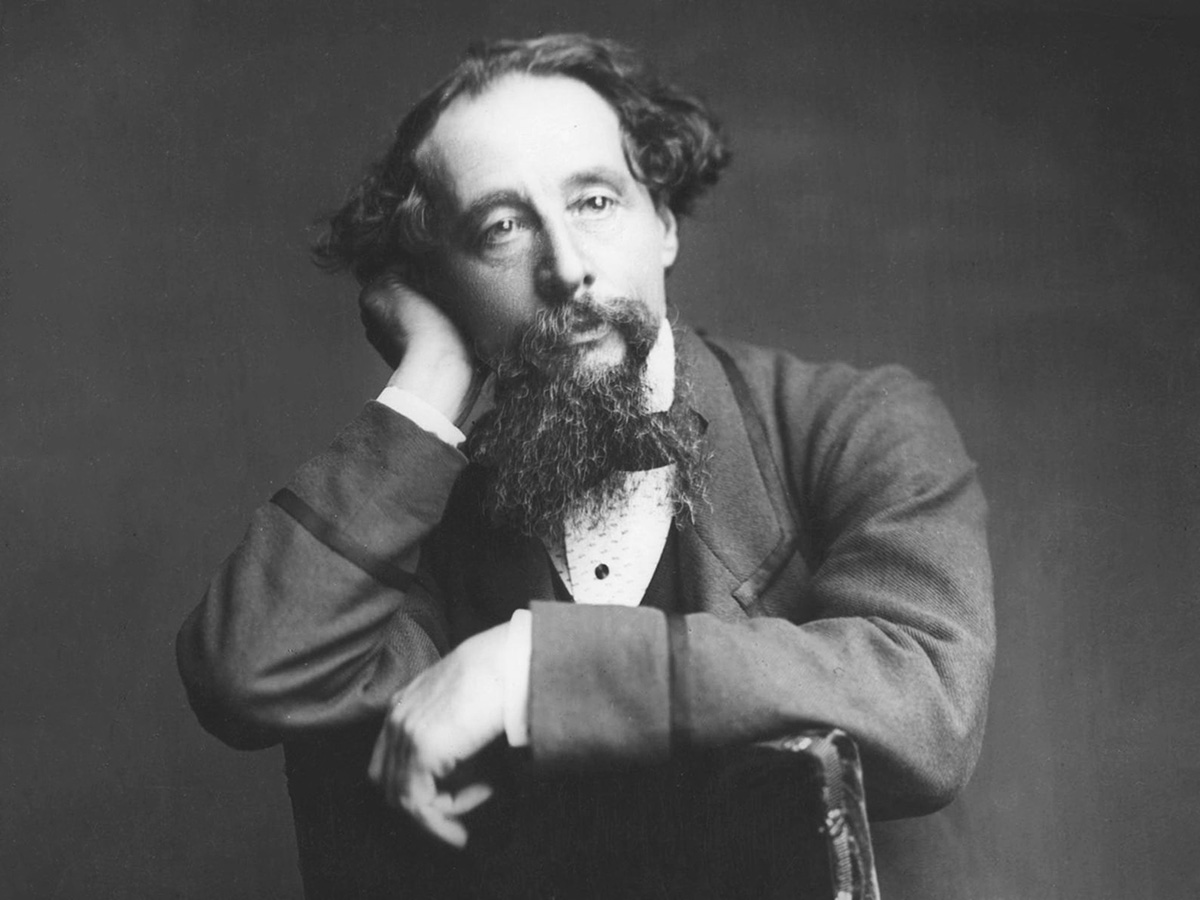

Two quotes pulled from Orwell’s classic 1940 essay on Charles Dickens.

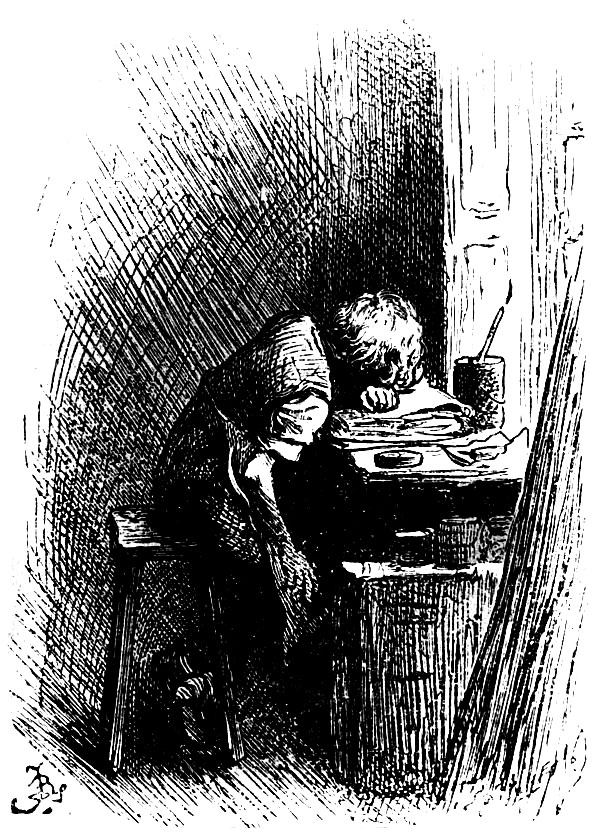

Why is it that Tolstoy’s grasp seems to be so much larger than Dickens’s — why is it that he seems able to tell you so much more about yourself? It is not that he is more gifted, or even, in the last analysis, more intelligent. It is because he is writing about people who are growing. His characters are struggling to make their souls, whereas Dickens’s are already finished and perfect. In my own mind Dickens’s people are present far more often and far more vividly than Tolstoy’s, but always in a single unchangeable attitude, like pictures or pieces of furniture. You cannot hold an imaginary conversation with a Dickens character … because Dickens’s characters have no mental life. They say perfectly the thing that they have to say, but they cannot be conceived as talking about anything else.

And a little further on:

What people always demand of a popular novelist is that he shall write the same book over and over again, forgetting that a man who would write the same book twice could not even write it once.