“The opposite of play is not work, it’s depression,” says Dr. Stuart Brown in this TED presentation on the importance of play. (The quote seems to originate with Brian Sutton-Smith.) I ran across this epigram yesterday in a blog post by Garr Reynolds called “The Secret to Great Work Is Great Play,” and a light bulb flashed on in my head.

I have been in an unproductive loop lately. About six weeks ago I submitted the manuscript for my third book. My editor loved the pages (the book will be released as a Random House “lead fiction” title, whatever that means) but, as always, she requested changes. I agreed with all her recommendations and was determined to finish the rewrites as quickly as possible. But the process has dragged on.

Why? Maybe I have been staring at the same project too long. I’m bored, ready to move on to a new book. Or maybe it’s the usual completion anxiety — the apprehensiveness that comes with releasing a manuscript out into the world, where its many flaws will surely be exposed.

Whatever the reason, a familiar vicious cycle has set in: the harder it is to write, the more I dread writing; the more I dread it, the harder it is to do. Mule that I am, I have responded to this dilemma the only way I know how — by working harder and harder and harder. But pulling the rope only makes the knot tighter.

So it was useful to be reminded that fiction-writing is a form of play — imaginative play. Which is not to say it is easy. Obviously it is not. But many kinds of play are not easy (weightlifting, crossword puzzles, classical piano). I have been writing for pleasure a lot longer than I have been doing it for money, but somehow the last few weeks I allowed my life’s passion to become drudgework. You cannot create that way. You have to relax. You have to bring a sense of play to your work. You have to enjoy the story you are creating even as you create it, because if it feels like drudgework to the writer, imagine how it will feel to the reader.

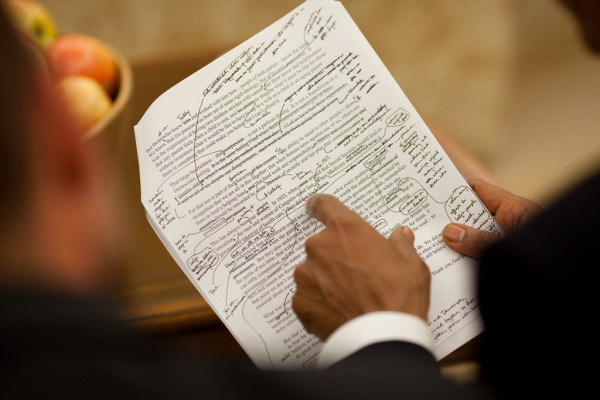

Image: My son Henry shows me how it’s done.