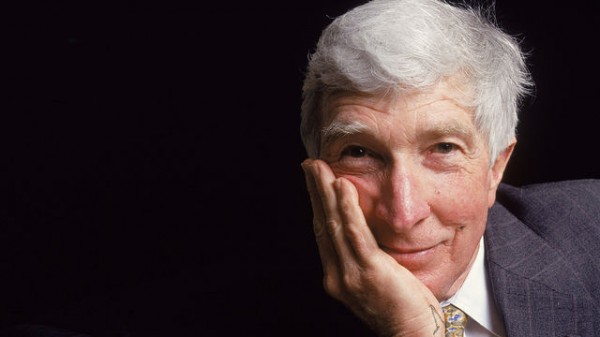

John Updike’s son David, also a writer, has a lovely piece in the Times’ Paper Cuts blog. It is a eulogy for his father which he delivered at a tribute in March at the New York Public Library. I found this passage particularly touching:

But for someone who was getting famous, my father didn’t seem to work overly hard: he was still asleep when we went to school, and was often home already when we got back. When we appeared unannounced, in his office — on the second floor of a building he shared with a dentist, accountants and the Dolphin Restaurant — he always seemed happy and amused to see us, stopped typing to talk and dole out some money for movies. But as soon as we were out the door, we could hear the typing resume, clattering with us down the stairs.

My own sons, now five and eight, perceive me the same way, I think. To kids (and others), a writer at work does not seem to be doing much. They can’t understand that I am hard at it whether I am typing like mad or staring blankly out the window. Maybe this is true of all desk-work. Well, at least I have this one thing in common with Updike.

I admit, I feel a strange, vaguely filial attachment to writers of my father’s generation, especially Roth, Updike and Doctorow, whose books I grew up reading. Anyway, read the whole Updike eulogy. You won’t be sorry.

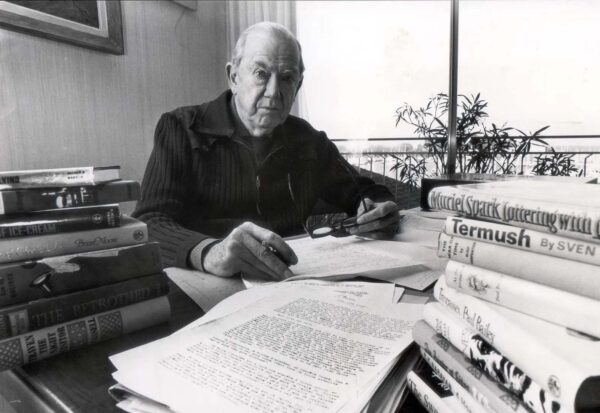

In the meantime, for all my fellow unmentored writers out there, here is Updike in 2004 with some fatherly advice for young writers.

The rest of the interview is here.