Just as a good man forgets his deed the moment he has done it, a genuine writer forgets a work as soon as he has completed it and starts to think about the next one; if he thinks about his past work at all, he is more likely to remember its faults than its virtues. Fame often makes a writer vain, but seldom makes him proud.

Archives for 2016

How Styron wrote

The previous summer, Styron had begun [The Confessions of Nat Turner]. He nudged a No. 2 pencil across sheets of yellow legal paper, each sentence polished before he moved on to the next. The most methodical of novelists, he demanded utter silence, even with small children in the house. He had a stone wall built in front to try to muffle the noise of passing vehicles, according to his daughter Alexandra in her 2011 memoir, Reading My Father. His pattern was all but inviolate. Up at noon, leisurely lunch or brunch with Rose. Push away from the table at two o’clock for a long walk with his dogs, while he organized his thoughts for the afternoon siege. Then, into the barn until he emerged at 7:30 with “my painful 600 words,” which he refined some more over a drink at the bar and then gave to Rose for typing, about two and a half pages in all. Once he was done he tinkered very little. “This guy does not revise heavily and start all over again,” says his longtime editor, Robert Loomis, aged 89. “Bill’s first draft was essentially his final draft.”

Sam Tanenhaus, “The Literary Battle for Nat Turner’s Legacy” (great read)

“My painful 600 words.” I know the feeling. It took William Styron four and a half years to complete The Confessions of Nat Turner.

“The Year of Lear”

Shakespeare became a god long ago. He exists outside history, eternal, unconfined by any particular historical moment. He is literally timeless. In The Year of Lear, James Shapiro swats away all the writer-god stuff and plunks us down with Shakespeare in grubby, plague-ravaged, terrorized London in 1606. It is probably as close as we can come to glimpsing the man himself; too little is known about Shakespeare’s life to reconstruct a proper biography. And for a writer like me, it is stirring to see Shakespeare grapple in his plays with the obsessions and anxieties of Jacobean England — fear of a bloody succession battle, the hunt for Catholic recusants, the Gunpowder Plot (the 9/11 of its day), witchcraft, demonic possession, on and on. Just a working writer at his desk, in a dirty, day-old shirt, his thoughts tossed around like all of us. It’s a great read.

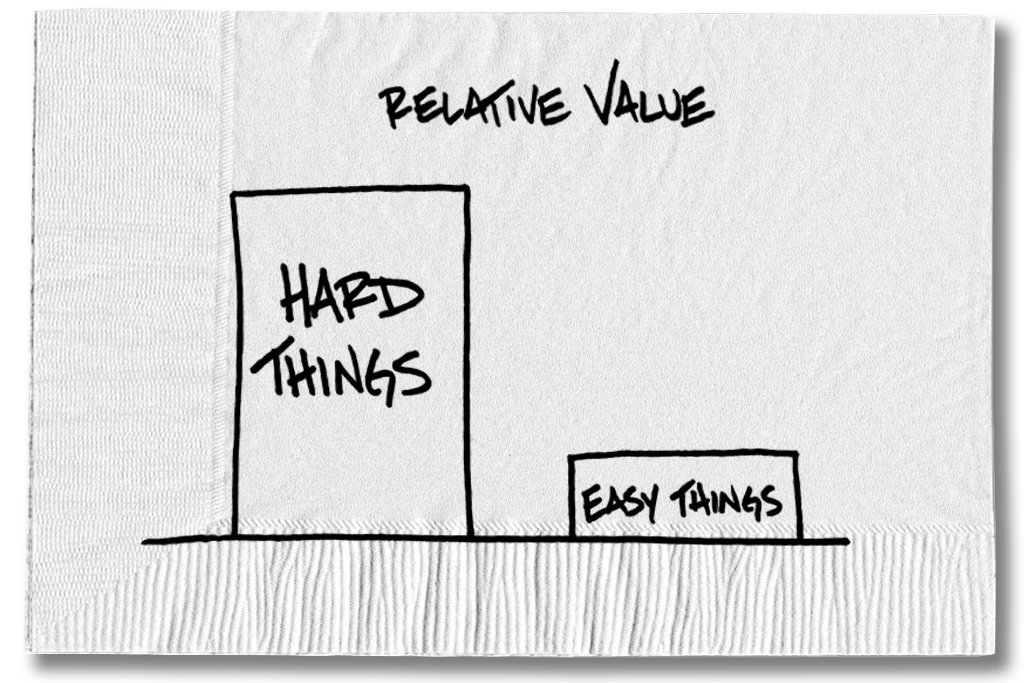

If it’s hard, why do it?

This graphic, from a story in the Times the other day, pretty well captures the appeal of novel-writing for me. You do it precisely because it’s difficult.

Writing as meditation

I see writing as a form of meditation, where I can let everything else fall away for a few moments and just stay with this one activity. It means I need to get my mind into the writing space, notice when the urge to go to distraction comes up, and not just automatically follow the urge. I can look within myself and let feelings flow out through the written word, or see the truths within me and try to channel those onto the page.

Leo Babauta, “Training To Be a Good Writer“

Quote of the day

I’m most in awe of novelists, who move sets, lights, scenery, and act out all the parts in your mind for you. My kind of writing requires collaboration with others to truly ignite. But I think of Dickens, or Cervantes, or Márquez, or Morrison, and I can describe to you the worlds they paint and inhabit. To engender empathy and create a world using only words is the closest thing we have to magic.

Horace: Artless art

“The art lies in concealing the art.”

Horace

On procrastination, good and bad

We tend to think of procrastination as a personal failing, even a moral flaw, a sin. For novelists in particular, marooned at our lonely desks and in our heads, facing enormous tasks and distant deadlines, procrastination is a besetting danger. The web makes the problem infinitely worse, with its little cruelty of turning the writer’s workspace, his computer screen, into an endless cabinet of wonders. Distraction is always just two clicks away.

There is now a small industry churning out advice on how to stay productive in the age of distraction, but it all boils down to this: put away your toys and get to work. In his wonderful The War of Art, Steven Pressfield advises, “Be a pro.” And that, honestly, is the bottom line. Just do it.

Personally, I try to live by that advice. By nature I am lazy and undisciplined, a lifelong procrastinator, so I rely on a set of formal strategies to stay focused. I work in a barren office, on an ancient ThinkPad T23 laptop that has no internet capability. I cripple my smart phone using various apps. (I fiddle constantly with how best to disable my phone during work hours, which, yes, I know.) When all else fails, I leave the damn phone at home.

Fellow weak-willed writers, I can’t say this strongly enough: do not burn energy resisting the temptation of the web. Just turn it off completely. Unplug. Research has shown that people who exhibit strong willpower are not better at resisting temptation; they simply do not expose themselves to temptation. They do not bravely refuse to eat the ice cream in the freezer; they never go down the frozen-food aisle in the supermarket in the first place.

Once I have unplugged from the web, I focus on starting. Not writing a whole novel or even a single scene, not writing for a certain period of time or hitting some daily word-quota. Just starting. As a writer, that is the most essential and difficult thing you will do: start. You must learn to start and start and start. Every morning, despite the awesome scale of the task, despite your own mounting anxiety, you must start. You will fail, of course. All writers fail. Most writers fail most of the time. Doesn’t matter. Get up, dust yourself off, and start again. If you start enough, in some small percentage of those attempts, you will achieve the blessed, transporting, trance-like state of flow that every writer treasures, and the residue of that deeply-focused work will be words on the page.

So that is my anti-procrastination strategy. In two words: unplug and start. I do not claim there is any special wisdom there, nor do these strategies work infallibly for me. I fail all the time, and I scourge myself for it. Probably you do, too. if you are a writer. It seems to be a universal feeling in this job. But failure is part of writing. Tomorrow you will try again. What choice is there? As Beckett said, “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

With all that said, I would like to suggest that some procrastination is actually good. Yes, good. Sometimes a writer resists writing not because he is lazy or careless, but because the passage just isn’t ready to be written. Hemingway famously said, “The most essential gift for a good writer is a built-in, shockproof, shit detector.” Sometimes the way your shit detector goes off is by refusing to allow you to write shit in the first place.