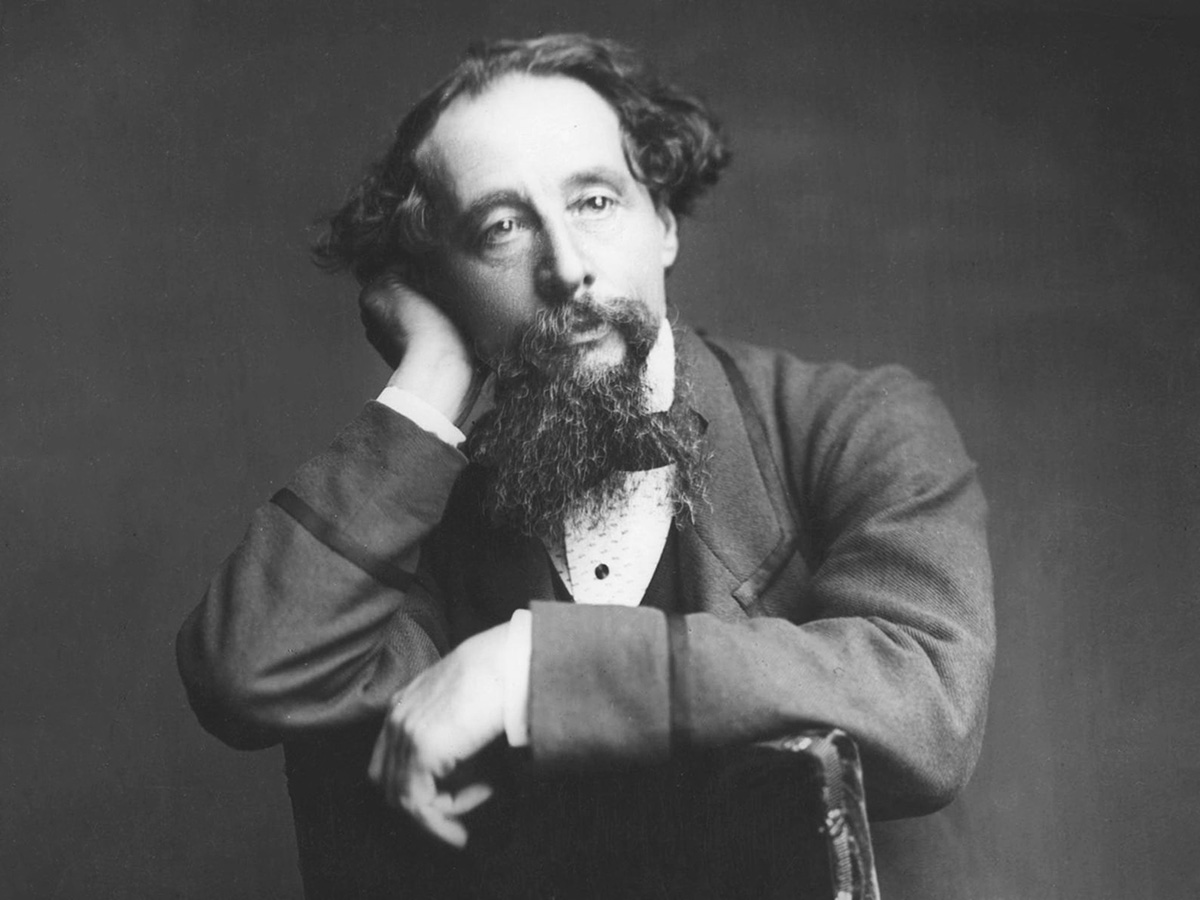

“No place affords a more striking conviction of the vanity of human hopes than a public library; for who can see the wall crowded on every side by mighty volumes, the works of laborious meditations and accurate inquiry, now scarcely known but by the catalogue…”

— Samuel Johnson, Rambler #106 (March 23, 1751) (source) (click that link at your peril — a fella could get lost in a place like that)