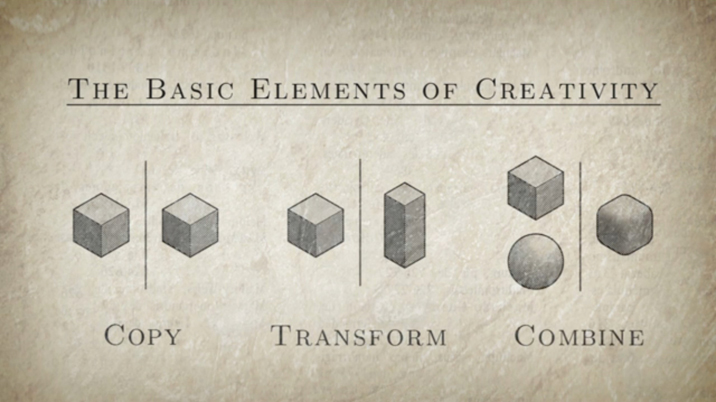

Creativity is not about making something out of nothing. It is about making something new out of old things. When we say that an artist creates, what we mean is that he refines, reshapes, remixes. He synthesizes. I am not creative, in the sense that I have no ability to manufacture novels out of thin air. I am an exceptional remixer.

Lately, desperate to get my new novel started, I have been suffering from a wrongheaded dread of influence, formula, and topicality, when in truth these are the very things I should be looking to. I have been suffering from a lack of input, starving the creative machine of fuel — ideas — then wondering why the engine will not start.

Wannabe writers ask, “Is there a book in me?,” then lose themselves in introspection, like a dog chasing its own tail. It is the wrong question. Look outward.

Image: Kirby Ferguson – “Everything Is a Remix.”