The next time I am tempted to whimper that my writing life is hard, I will think of William Manchester’s epic struggle, from 1963-1966, to write a definitive account of the JFK assassination, as described in this month’s Vanity Fair.

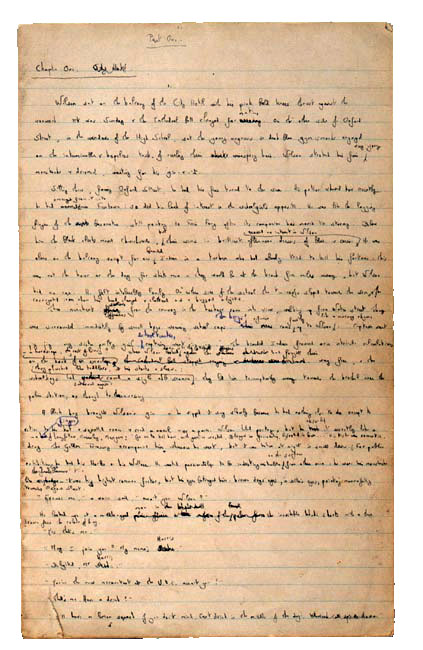

He was becoming unhinged. Once, while working on a homework assignment, 15-year-old John [Manchester’s son] asked his father what day it was. Manchester replied without thinking, “November 22.” On another occasion, he acted strangely during an interview with a friend of Jacqueline’s. Manchester had gotten up to look out the window, convinced that he saw something moving in the bushes. “I’ve been followed ever since I began this book,” he said. … By the second anniversary of the assassination, Manchester began to crack. “I had no appetite — for food, for beauty, for life. I slept fitfully; when I did drift off, I dreamt of Dallas. I was gripping my Esterbrook [fountain pen] so hard that my thumb began to bleed under the nail. It became infected … marring the manuscript pages with blood.”

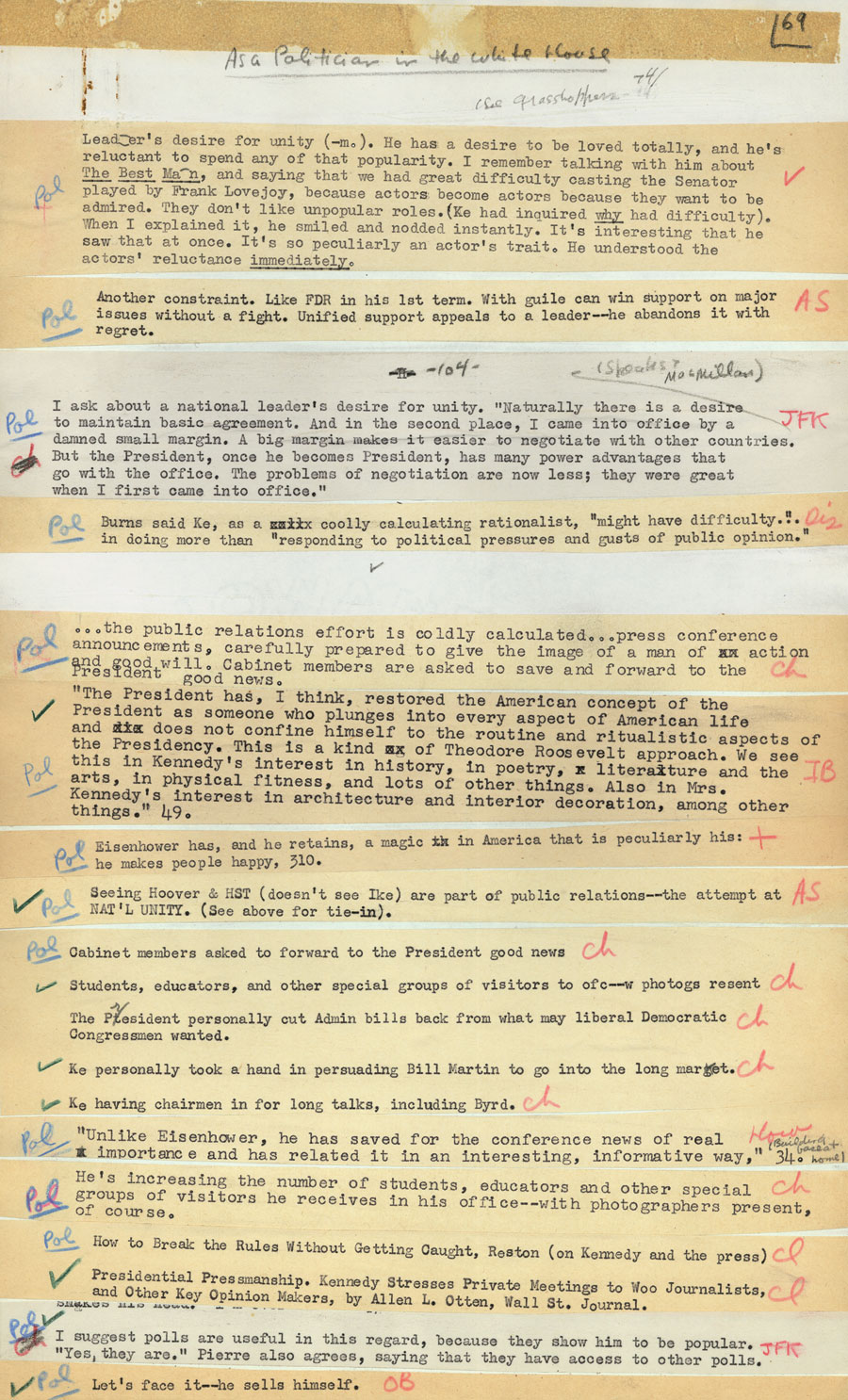

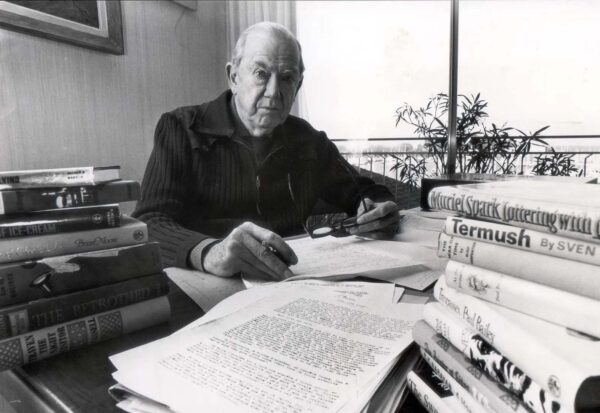

Below is a cut-and-paste page from Manchester’s manuscript. (Click image to view full size.) An image of Manchester in 1964 is here.