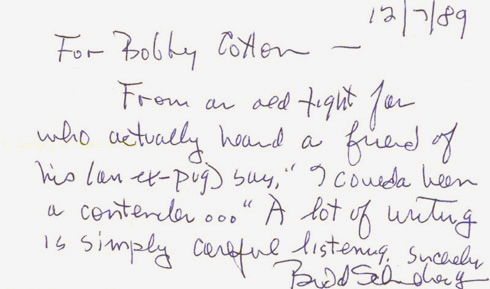

A note from screenwriter Budd Schulberg to a fan, jotted on the back of an index card, explains the origin of the famous line from “On the Waterfront.” The note reads:

12/7/89

For Bobby Cotton —

From an old fight fan who actually heard a friend of his (an ex-pug) say, “I coulda been a contender…” A lot of writing is simply careful listening.

Sincerely,

Budd Schulberg

Now, about that one-way ticket to Palookaville…