I stopped by the new exhibit today at the Howard Yezerski Gallery on Harrison Avenue, “Boston Combat Zone: 1969-1978.” The gallery and the show both are small but well worth a visit, even on a raw, rainy day like today.

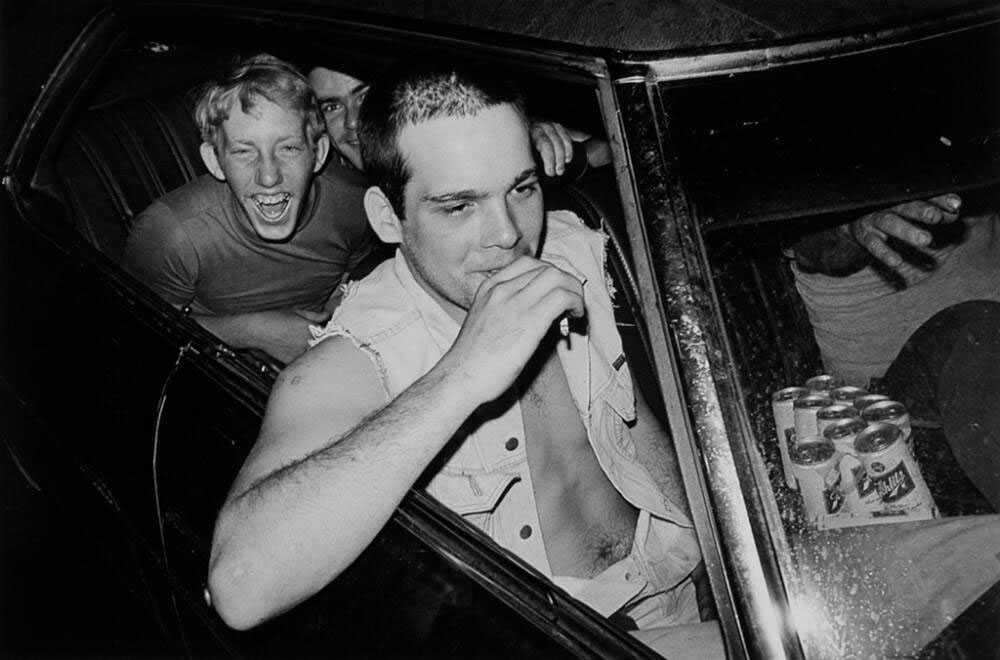

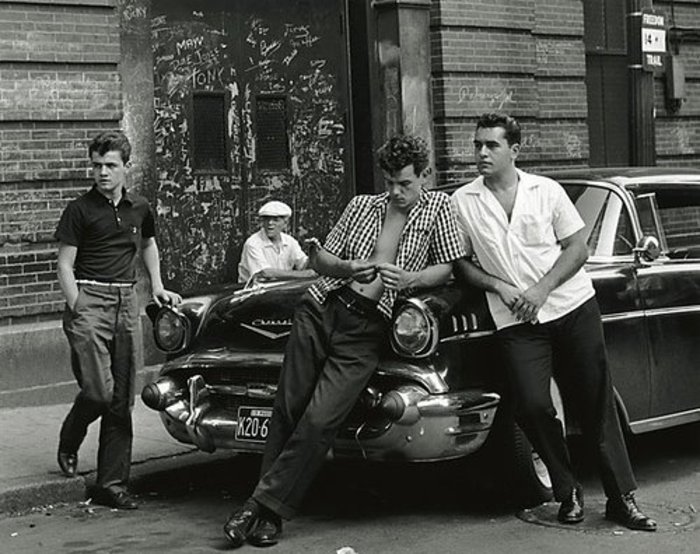

The exhibit gathers together black-and-white photographs by Roswell Angier, Jerry Berndt, and John Goodman. The photographs all show the people of the Combat Zone — hookers, strippers, pimps, lonelyhearts. Some are posed portraits, some are candid, journalistic shots. There are no empty compositions, no unpeopled streets. It is all real faces, real bodies. The subject is what in the Zone was called The Life.

I have been fascinated by the Combat Zone for a long time and always wanted to write about it. (I did write a short story about it once. More info here.) When my third book is finished — I hope to send the manuscript off to my publisher next week — I intend to pitch my editor on a novel set in the Combat Zone for book four. Maybe this exhibit is a good omen.

In the meantime, if you’re in the area I recommend the show. I have done quite a bit of research on life in the Combat Zone and I have never seen so many images, especially such evocative and beautiful ones, in one place.

Photo: John Goodman, “The Schlitz Boys,” 1978 (gelatin silver print, 16″ x 20″). Click image to view larger.

Matt Kish, whose

Matt Kish, whose